Wuthering Heights

Fennell’s take on the classic novel lacks the edge it aspires to.

When I think of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, I think of Cathy’s ghost reaching through the window, begging to be let back into the house because she’s so cold. Some of this is probably Kate Bush’s fault—I can’t help but hear Cathy’s cry of “Let me in!” in Bush’s soprano. The image of a woman haunting the outside edges of the house neatly sums up the book’s deeper themes, with Brontë plainly discussing issues of abandonment and abuse, societal constructs of gender and race, doomed love and family feuds, all as desolate as the moors on which the story takes place. The newest adaptation from writer/director Emerald Fennell brushes most of these ideas aside in favor of the tragic romance at its core. It’s Heathcliff and Cathy, but it isn’t the full story.

Fennell takes Brontë’s loaded image of a reaching hand and reinterprets it simply as the hold that Heathcliff (played by Owen Cooper as a child and Jacob Elordi as an adult) has on Cathy (Charlotte Mellington as a child, Margot Robbie as an adult). Rather than reaching through a window, Heathcliff reaches out from his hiding place underneath a bed, his hand clamped around Cathy’s ankle as she sits with her bare feet on the floor. It’s a good image, repeated multiple times as the couple grow from children to adulthood. It wordlessly communicates Fennell’s focus on the romance between two lonely individuals.

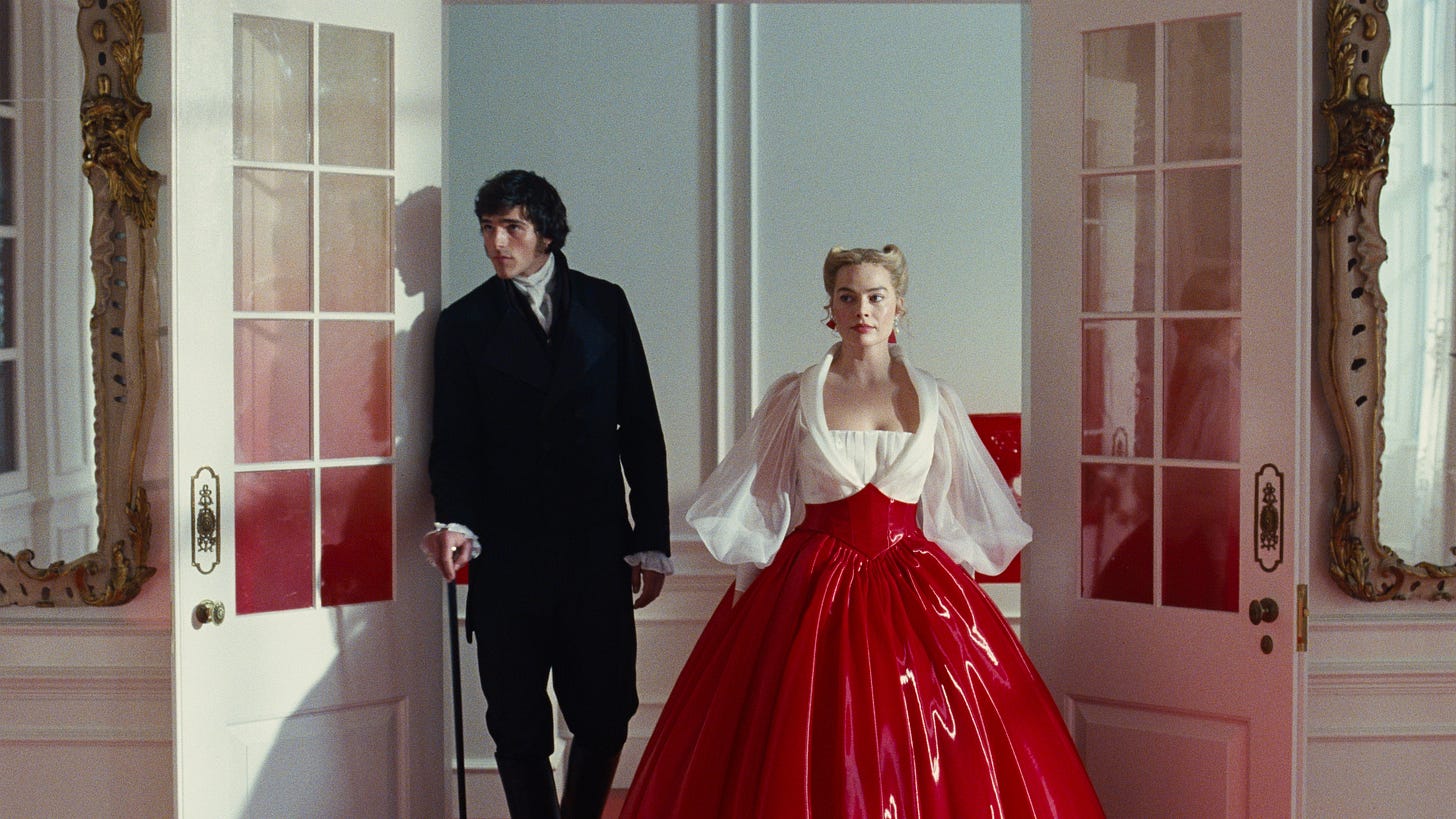

Fennell’s version of “Wuthering Heights” (fussy quotation marks and all) takes place in a world of bright colors and a grim tone: a Tumblr aesthetic recreated on screen. Charli xcx’s soundtrack songs speak only to the events of the plot without commenting or expanding on it. “I think I’m gonna die in this house,” she sings over the opening credits, but we already knew this was a doomed relationship before the music started. The titular house is pushed up into a crevice of forbidding black stone, impossibly tall and constantly damp, a contemporary take on German Expressionist backgrounds. The costumes (designed by Jacqueline Durran) all convey a sensation of slickness: Cathy’s gowns are made of shiny, stiff cloth, with elements of plastic and latex. The contemporary take on the story is even sewn into the dresses. They are analogues to the Converse sneakers in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette but without the accompanying sociopolitical commentary. Fennell’s movie is about class in the same way her previous movies are about class. She’s aware it exists. She doesn’t know what to do about her poor characters, aside from feeling pity for them.

Fennell’s script isn’t interested in the thematic complexities surrounding its central couple, either; she cares only about the question of true, doomed love. She juxtaposes a pair of rhyming images involving the scars on Heathcliff’s back and a series of cuts on Cathy’s. His scars have been raised by abuse and hers by a corset she insists on wearing too tight for her wedding to a rich man, Mr. Linton (Shazad Latif). Heathcliff has been harmed for love; she chooses to harm herself in making a vow to a man she doesn’t love in Heathcliff’s absence. But both images remain married stubbornly to individual choice without contemplating the paths that could have led these individuals to that decision point in the first place.

I prefer adaptations that refuse to be carbon copies of their source material, but only if they use that text as a jumping-off point for more interesting thematic explorations. Instead of going further, Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” retreats into a corner. The film is trapped in place, unable to see the larger community for the choices of its individual characters. It is obsessed with Robbie’s face and Elordi’s height and not much else. Both are game actors; neither is given the chance to play to the best of their abilities. We’ve seen Elordi’s stature and charm used much better in Coppola’s Priscilla. Robbie looks like a holiday-edition Barbie in some of her gowns, a touch that made me long for her chemistry with Ryan Gosling.

Tragically, this version of the story mistakes the heat of physical intimacy for interpersonal chemistry. Fennell keeps crashing her characters into each other as though physical intimacy is the only point of a relationship. Even worse, she transforms some of the book’s seedier subplots into notes of anachronistic empowerment. A bad marriage between Heathcliff and Cathy’s sister-in-law Isabella (Alison Oliver) is transformed from an abusive relationship in the book to a consensual one. In Fennell’s telling, Isabella likes it rough: an attempt to grant the character agency that also defangs Heathcliff’s act of revenge in marrying her. Fennell wants her characters to behave badly, but she doesn’t want them to be bad people.

Say what you will about the novel, but it knows what it’s about, and it takes no prisoners in being about it. Fennell’s adaptation zeroes in on the romance at the heart of the story, desperate to introduce an edge for contemporary audiences that, in the telling, sands down the characters’ more troubling burs. Despite its contemporary costuming and set design, it’s a thin imitation of the wildness that Brontë found out on the moors. —Sarah Welch-Larson

★☆☆☆

“Wuthering Heights” is in theaters everywhere now.